THE NIGHT WAS ALMOST OVER; the sky was green and grey in the east, and snowflakes were ghosting around Asgard. Loki and only Loki saw Freyja leave Sessrumnir. Her cats slept undisturbed by the hearth; her chariot lay unused; in the half-light she set off on foot towards Bifrost. Then the Sly One’s mind was riddled with curiosity; he wrapped his cloak around him and followed her.

THE NIGHT WAS ALMOST OVER; the sky was green and grey in the east, and snowflakes were ghosting around Asgard. Loki and only Loki saw Freyja leave Sessrumnir. Her cats slept undisturbed by the hearth; her chariot lay unused; in the half-light she set off on foot towards Bifrost. Then the Sly One’s mind was riddled with curiosity; he wrapped his cloak around him and followed her.

HRAUDUNG, KING OF THE GOTHS, had two sons, Agnar and Geirrod. One day when Agnar was ten winters old and Geirrod eight, the brothers gathered their tackle and went out rowing in the hope of landing some fish. But soon the wind began to bluster, and the boys were driven so far out to sea that they lost sight of land. The night-shadow grew long, and in the darkness the small boat tossed and spun and was smashed to pieces on a rocky shore. Standing bedraggled in the darkness, with waves breaking around them, Agnar and Geirrod had not the least idea where they were.

HRAUDUNG, KING OF THE GOTHS, had two sons, Agnar and Geirrod. One day when Agnar was ten winters old and Geirrod eight, the brothers gathered their tackle and went out rowing in the hope of landing some fish. But soon the wind began to bluster, and the boys were driven so far out to sea that they lost sight of land. The night-shadow grew long, and in the darkness the small boat tossed and spun and was smashed to pieces on a rocky shore. Standing bedraggled in the darkness, with waves breaking around them, Agnar and Geirrod had not the least idea where they were.

FREYR HAD NO BUSINESS to be in Odin’s hall, Valaskjalf. And he had no right at all to sit in the high seat Hlidskjalf and look out over all the worlds. That was the right only of Odin and his wife Frigg.

Freyr narrowed his eyes and looked north into Jotunheim. What did he see? A large handsome hall belonging to the giant Gymir. And what did he see next? A woman coming out of this hall. Her name was Gerd — she was Gymir’s daughter. She seemed to be made of light, or clothed in sparkling light. When she raised her arms to close the hall doors, the dome of the sky and the sea surrounding the earth at once grew brighter. Because of her, all the worlds were hidden in a flash of brilliant icy light.

SOMEHOW THE SHAPE-CHANGER got into Sif’s locked bedroom. Smiling to himself, he pulled out a curved knife and moved to her bedside. Thor’s wife was breathing deeply, evenly, dead to worldly sorrows. Then Loki raised his knife. With quick deft strokes he lopped off Sif’s head of shining hair — her hair which as she moved rippled and gleamed and changed from gold to gold like swaying corn. Sif murmured but she did not wake; the hair left on her cropped head stuck up like stubble.

SOMEHOW THE SHAPE-CHANGER got into Sif’s locked bedroom. Smiling to himself, he pulled out a curved knife and moved to her bedside. Thor’s wife was breathing deeply, evenly, dead to worldly sorrows. Then Loki raised his knife. With quick deft strokes he lopped off Sif’s head of shining hair — her hair which as she moved rippled and gleamed and changed from gold to gold like swaying corn. Sif murmured but she did not wake; the hair left on her cropped head stuck up like stubble.

BEYOND THE GIRDLE of flint-grey water and the loveless lava flows, beyond the burning blue crevasses, lay Thrymheim, the storm-home of Skadi and her father Thiazi. It was a wonder that the hall withstood the charges of the wind and the batteries of hail.

BEYOND THE GIRDLE of flint-grey water and the loveless lava flows, beyond the burning blue crevasses, lay Thrymheim, the storm-home of Skadi and her father Thiazi. It was a wonder that the hall withstood the charges of the wind and the batteries of hail.

VERY EARLY ONE SUMMER MORNING, Odin, Loki and Honir crossed into Midgard, happy in one another’s company, and in- tent upon exploring some part of the earth not already known to them.

VERY EARLY ONE SUMMER MORNING, Odin, Loki and Honir crossed into Midgard, happy in one another’s company, and in- tent upon exploring some part of the earth not already known to them.

In the pale blue, almost pale green light that gives an edge to everything, the three friends crossed a desolate reach of grit, patrolled only by the winds. Before men in Midgard had stirred and woken, the gods were striding over scrubby, undulating ground. Then they tramped round a great mass of spiky, dead, dark rock, and headed for the summit of a conical mountain.

THE MOTHER OF SLEIPNIR was also the father of three appalling children. Not content with his faithful wife Sigyn, Loki sometimes took off for Jotunheim; the long-legged god hurried east and spent days and nights on end with the giantess Angrboda.

THE MOTHER OF SLEIPNIR was also the father of three appalling children. Not content with his faithful wife Sigyn, Loki sometimes took off for Jotunheim; the long-legged god hurried east and spent days and nights on end with the giantess Angrboda.

Loki and Angrboda had three monstrous offspring. The eldest was the wolf Fenrir; the second was Jormungand, greatest of serpents; and the third was a daughter called Hel. Even in a crowd of a thousand women, Hel’s looks were quite likely to single her out : her face and neck and shoulders and breasts and arms and back, they were all pink; but from her hips down, every inch of Hers skin looked decayed and greenish-black.

WHEN THE AESIR and the Vanir had made a truce, and settled terms for a lasting peace, every single god and goddess spat into a great jar. This put the seal on their friendship, and because the Aesir were anxious that no one should forget it, even for one moment, they carried off the jar and out of the spittle they fashioned a man.

Listen! Who can hear the sound of grass growing? The sound of wool on a sheep’s back, growing?

Who needs less sleep than a bird?

Who is so eagle-eyed that, by day and by night, he can see the least movement a hundred leagues away?

Heimdall and Heimdall and Heimdall.

But who could tell it was Heimdall, that figure on the seashore? The guardian of the gods left his horn Gjall safe in Mirmir’s spring; and he left Gulltop, his golden-manned stallion, behind the stable door; and he strode alone across the flaming three-strand rainbow bridge from Asgard to Midgard.

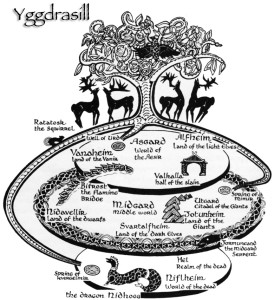

The Axis of the world was Yggdrasill. That ash soared and its branches fanned over gods and men and giants and dwarfs. It sheltered all creation. One root dug deep into Niflheim and under that root the spring Hvergelmir seethed and growled like water in a cauldron. Down there the dragon Nidhogg ripped apart corpses. Between mouthfuls, he sent the squirrel Ratatosk whisking up the trunk from deepest earth to heaven; it carried insults to the eagle who sat on the topmost bough, with a hawk perched on its brow. And Nidhogg was not content with corpses; he and his vile accomplices gnawed at the root of Yggdrasill itself, trying to loosen what was firm and put an end to the eternal.

The Axis of the world was Yggdrasill. That ash soared and its branches fanned over gods and men and giants and dwarfs. It sheltered all creation. One root dug deep into Niflheim and under that root the spring Hvergelmir seethed and growled like water in a cauldron. Down there the dragon Nidhogg ripped apart corpses. Between mouthfuls, he sent the squirrel Ratatosk whisking up the trunk from deepest earth to heaven; it carried insults to the eagle who sat on the topmost bough, with a hawk perched on its brow. And Nidhogg was not content with corpses; he and his vile accomplices gnawed at the root of Yggdrasill itself, trying to loosen what was firm and put an end to the eternal.